Super Mario World Physics

Super Mario!

Arguably one of the greatest video game series of all time, I spent countless hours playing these games as a kid. One thing I always particularly loved about the games is that the kinematics / physics of Mario’s motion were just so.. fun! Not necessarily that they felt real, but when you ran, you ran fast. When you jumped, you jumped high, etc. I think this is a problem that I have with numerous other platforming games.. yea, sure, the gameplay can be fun, but moving around just seems so… boring in comparison to Mario.

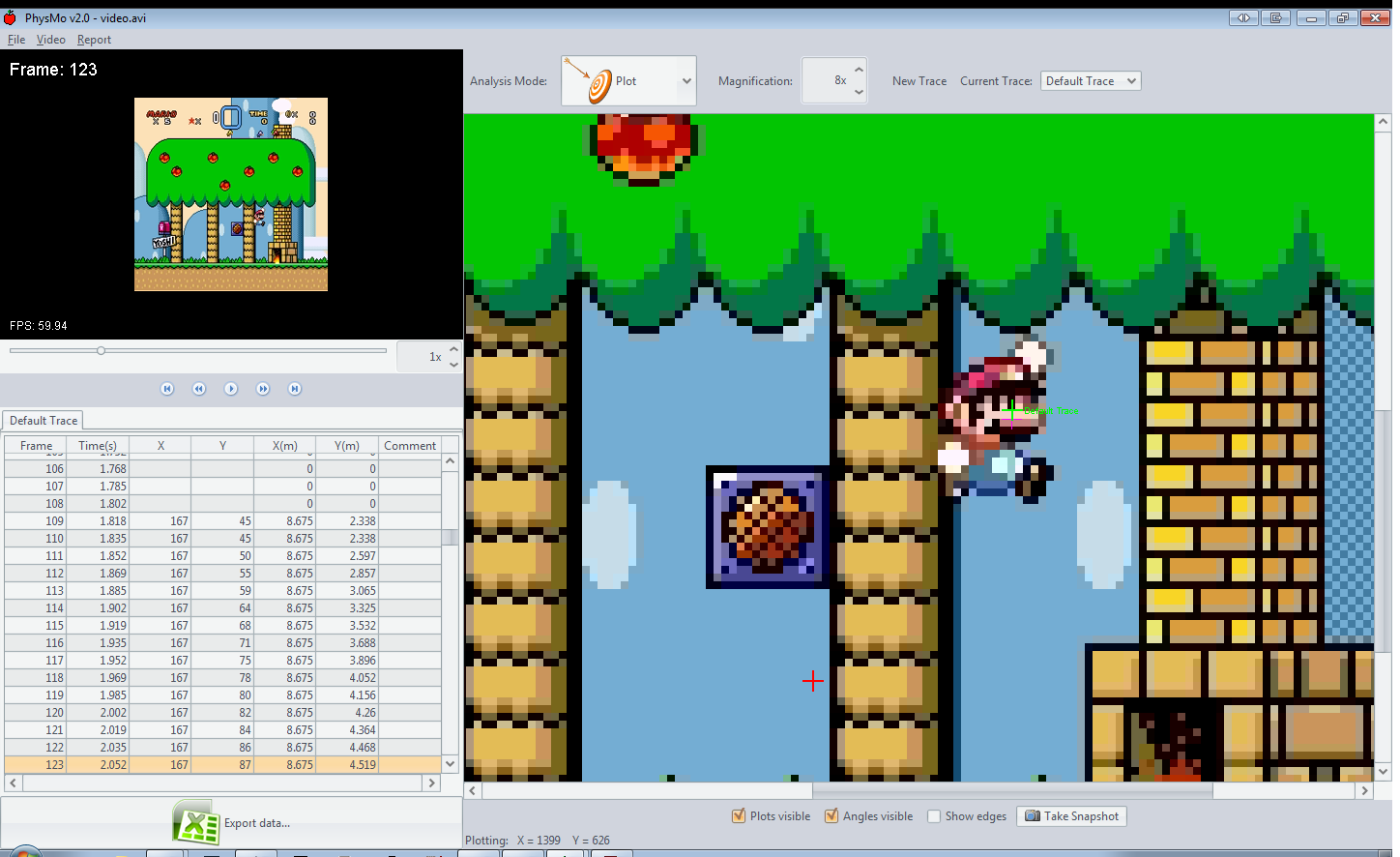

Since I’ve started dabbling around with my own demos and games lately, I figured it would be necessary for me to capture that sense of kinematic joy. Since I couldn’t find any definitive break-downs of Super Mario physics online (though I’ll be honest, I didn’t look too far), I decided it would be simple enough for me to do my own investigation. Thankfully, the process turned out to be a lot simpler than I was expecting thanks to the tools I used - ZSNES, MPlayer, PhysMo, and Matlab (though you could just as easily use GNU Octave instead of Matlab). The process I used went like this:

- Record a video of Mario going through his various motions using ZSNES and mencoder

- Import the video into PhysMo, and analyse the motion

-

Calibrate the analysis by defining Mario’s height as 1 m

-

Pick a non-deforming location on Mario’s sprite, then follow that point around in time and space, recording where it goes as Mario moves around

-

Export the results to be analysed elsewhere

-

-

Import the motion capture results into Matlab and perform regression analyses on them to figure out the constants of motion

A screenshot of the excel output from Mario jumping using motion analysis software

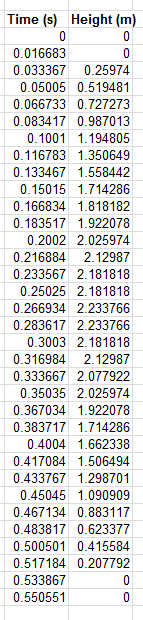

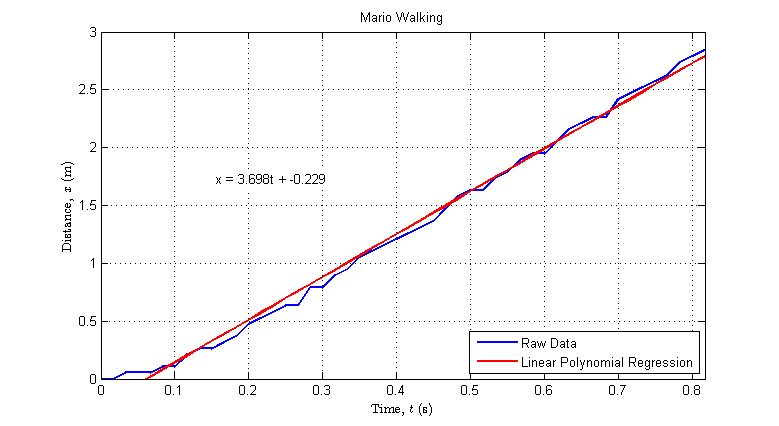

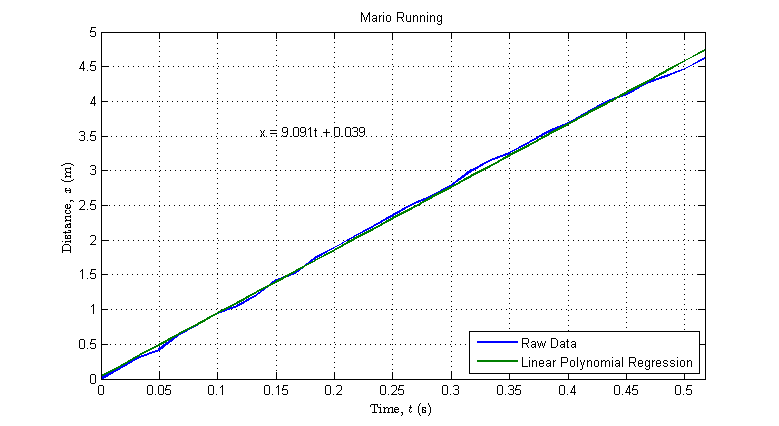

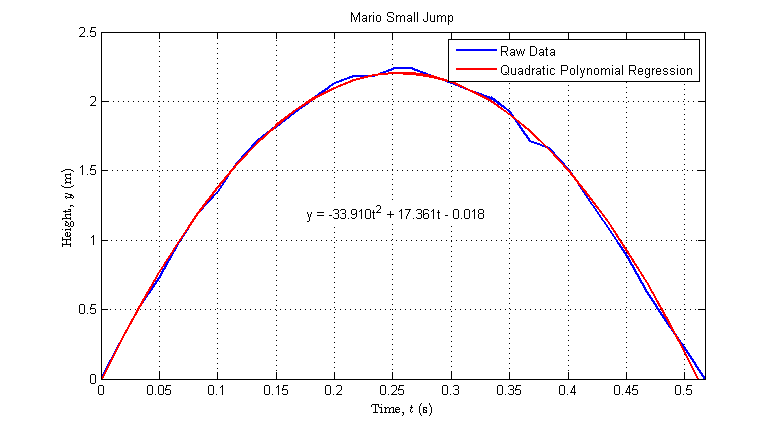

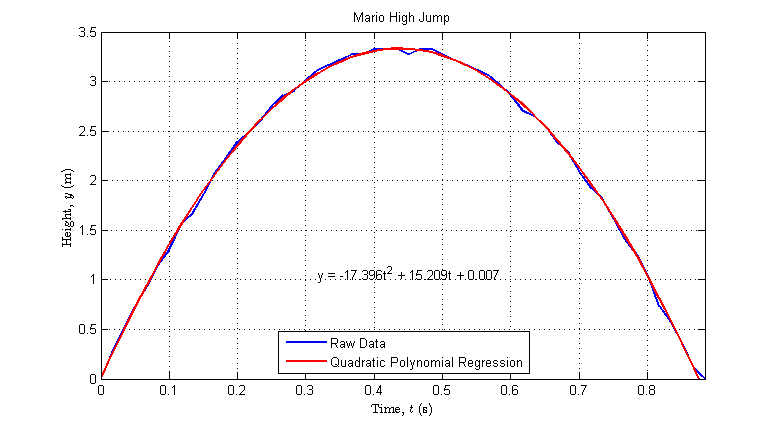

If you want to try this yourself, it’s certainly easy enough to do and figure out, but more likely you’re just interested in seeing some of the results I found. Here are the plots of the 5 basic motions I examined (walking, running, jumping, high-jumping, and following off a ledge):

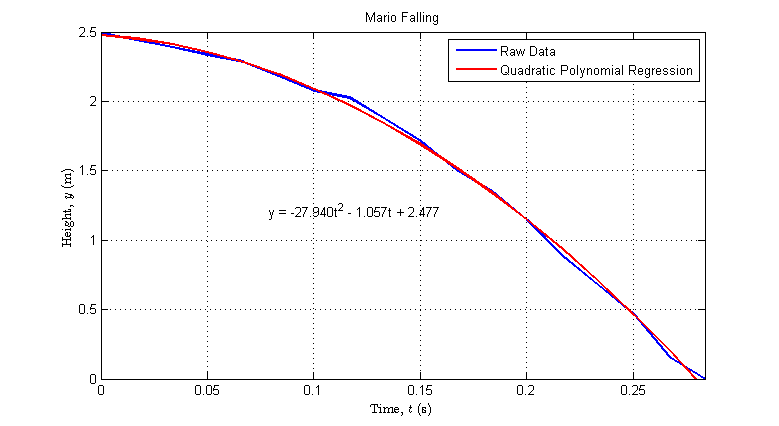

In each of the plots above I’ve included a simple linear regression analysis based on the physical model that makes sense - basically, for vertical movement a quadratic equation indicating constant gravity / acceleration, and a linear equation for horizontal movement indicating constant horizontal movement speed. For the relatively simple motion that we see here, this is all we really need, once we know a thing or two about Newton’s laws of motion and calculus - which I’ll quickly go over so you know what I’m talking about.

Basically, when thinking about motion, there are a couple key relationships that exist - the velocity of the motion is the derivative with respect to time (rate of change) of the position of the object, and the acceleration of the motion is the derivative of the velocity with respect to time:

Then, assuming we have a constant acceleration due to gravity (in the real world this acceleration is 9.81 m/s^2), we can figure out what the regression coefficients in the above analyses mean:

Applying this math to the regression coefficients that I calculated, we find that the coefficient in front of the t² term is half of gravity, while the coefficient in front of the t term is the “jump” velocity (we can ignore the y_0 parameter, as it really doesn’t mean much here). Using this, I found three separate gravities and push-off velocities, depending on the scenario (assuming short-Mario is 1m tall):

- When jumping regularly, Mario experienced a gravity of 67.82 m/s² (6.9 times Earth gravity). Here he had a push-off velocity of 17.36 m/s.

- When high-jumping, Mario experienced a gravity of 34.79 m/s² (3.5 times Earth gravity). Here he had a push-off velocity of 15.21 m/s.

- When falling off a ledge, Mario experienced a gravity of 55.88 m/s² (5.7 times Earth gravity).

As for running, Mario seemed to follow a perfectly constant run velocity pattern (as is expected, really). When walking, he moved at a speed of about 3.7 m/s, and when running, moved at a speed of about 9.1 m/s.

Now, it is a good idea to take these results with a grain of salt - I did the whole experiment and analysis in only one shot, with one trial for each type of motion, and made a few assumptions about the nature of the motion as well. That said, these values should give you a good starting point to produce “fun” motion in your games! Also, of course, Mario is the full property of Nintendo (or whoever the owner of it is), and I do not claim to possess ownership or even inside knowledge of the Mario name, game, physics, programming, etc. I do own a copy of game, which I still play occasionally (no emulator will ever be able to replace the feel of holding that plastic controller in your hand, sitting in your couch in front of the TV!), but that’s about it.